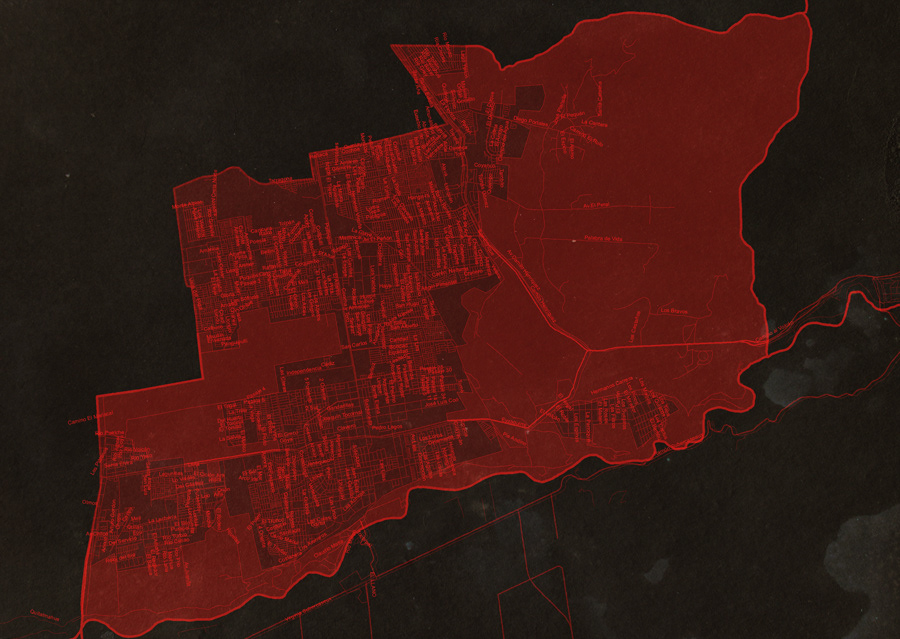

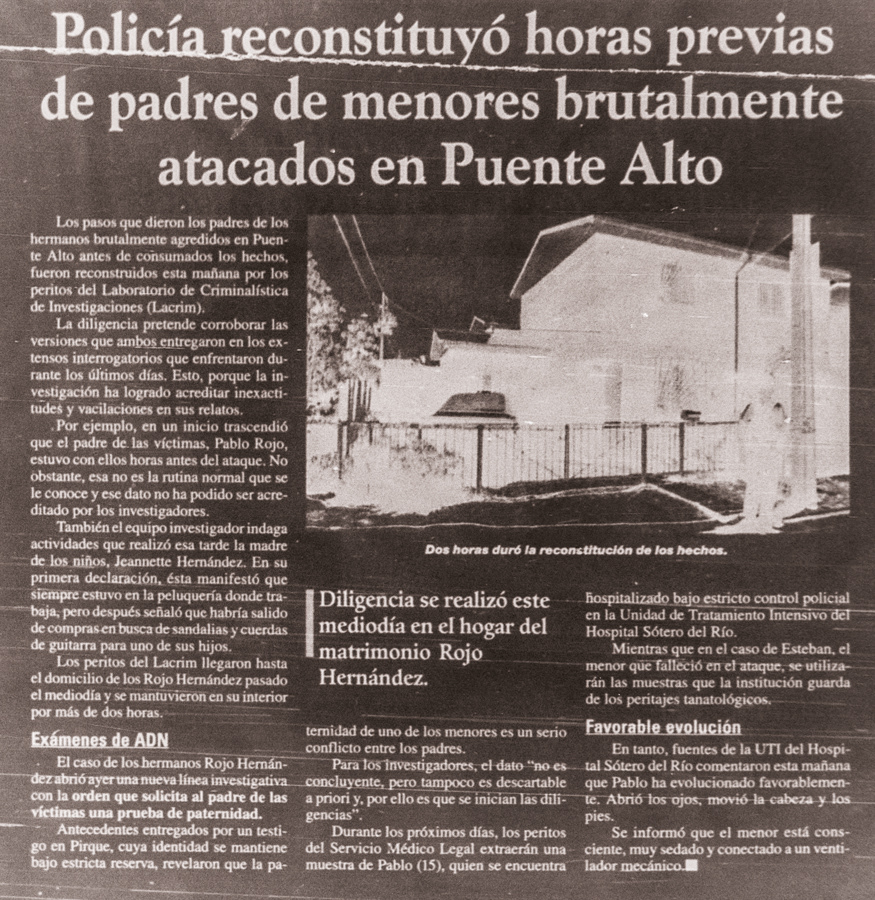

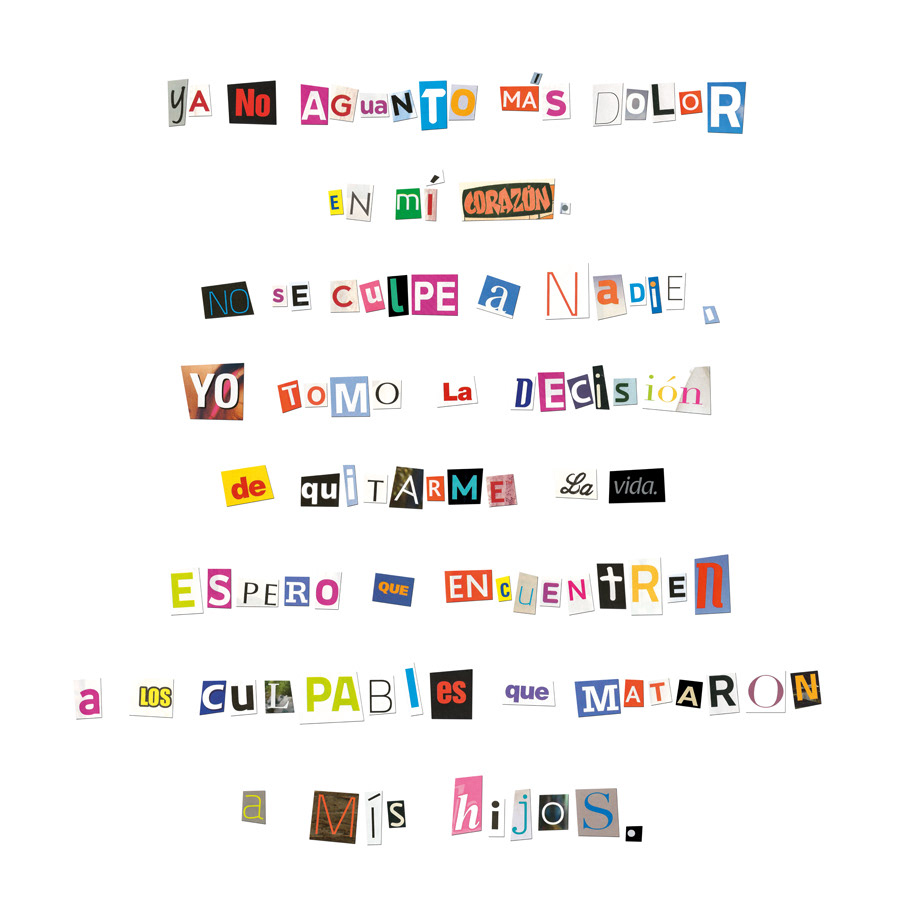

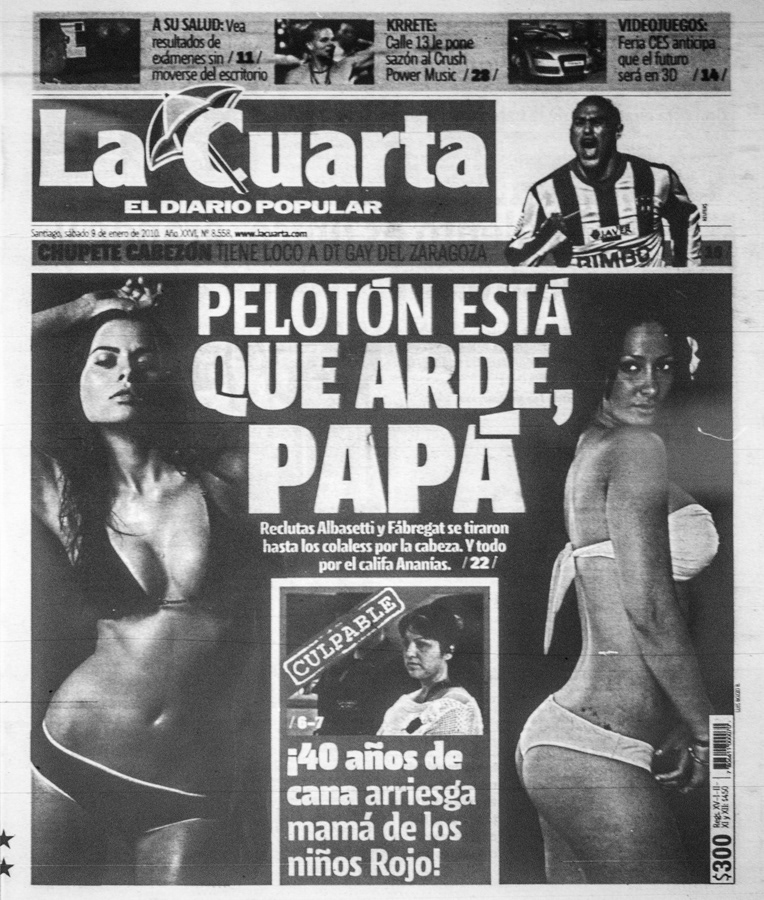

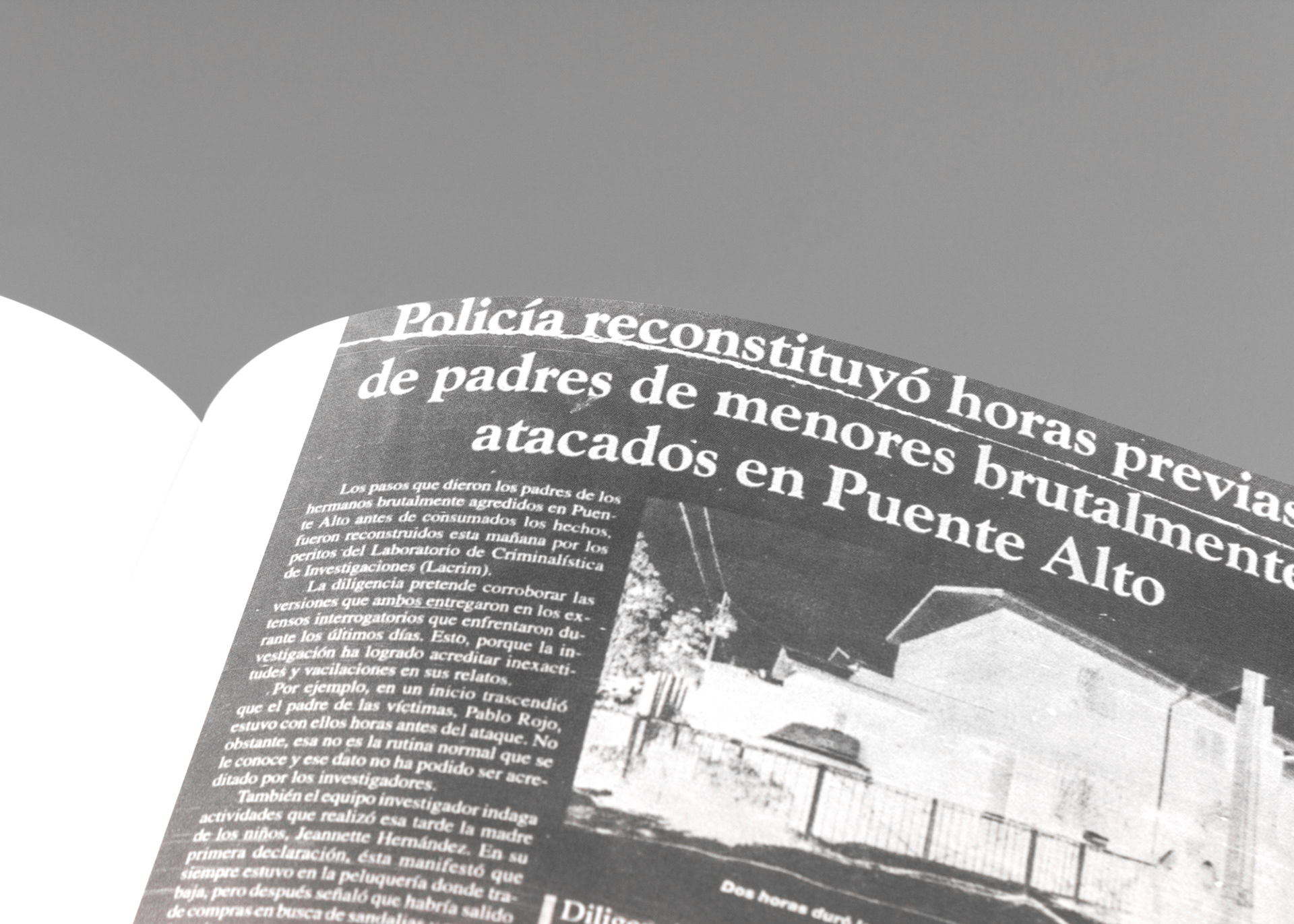

MEDEA (2017) narrates the gestation, development, and outcome of the crime of the Rojo brothers, tragedy that took place in 2008, in the district of Puente Alto, Santiago de Chile. It was here where the murders of Esteban Rojo (6) and the frustrated homicide of Pablo Rojo (15) were consummated. After a year of police investigation and expertise, the crime took a substantial turn from the contradictions detected in the children's mother, Jeannette Hernandez Castro, who, in an act of deep detachment and cruelty, became the author of crime. Jeanette, victim of her sickly jealousy, reacted in revenge against her spouse, Pablo Rojo Rodriguez, to whom she attributed an alleged infidelity with popular singer Miriam Peña, alias "la Rancherita”.

In April 2010, Jeannette Hernández Castro was convicted as the perpetrator of the crimes of parricide and frustrated parricide, and sentenced to twenty and twelve years' imprisonment respectively, in one of the most shocking cases in Chilean police blotter. The event echoes the Greek myth of Medea; who murdered her two children in revenge against her lover, Jason, after abandoning her for another woman, despite their promise of eternal love.

In April 2010, Jeannette Hernández Castro was convicted as the perpetrator of the crimes of parricide and frustrated parricide, and sentenced to twenty and twelve years' imprisonment respectively, in one of the most shocking cases in Chilean police blotter. The event echoes the Greek myth of Medea; who murdered her two children in revenge against her lover, Jason, after abandoning her for another woman, despite their promise of eternal love.

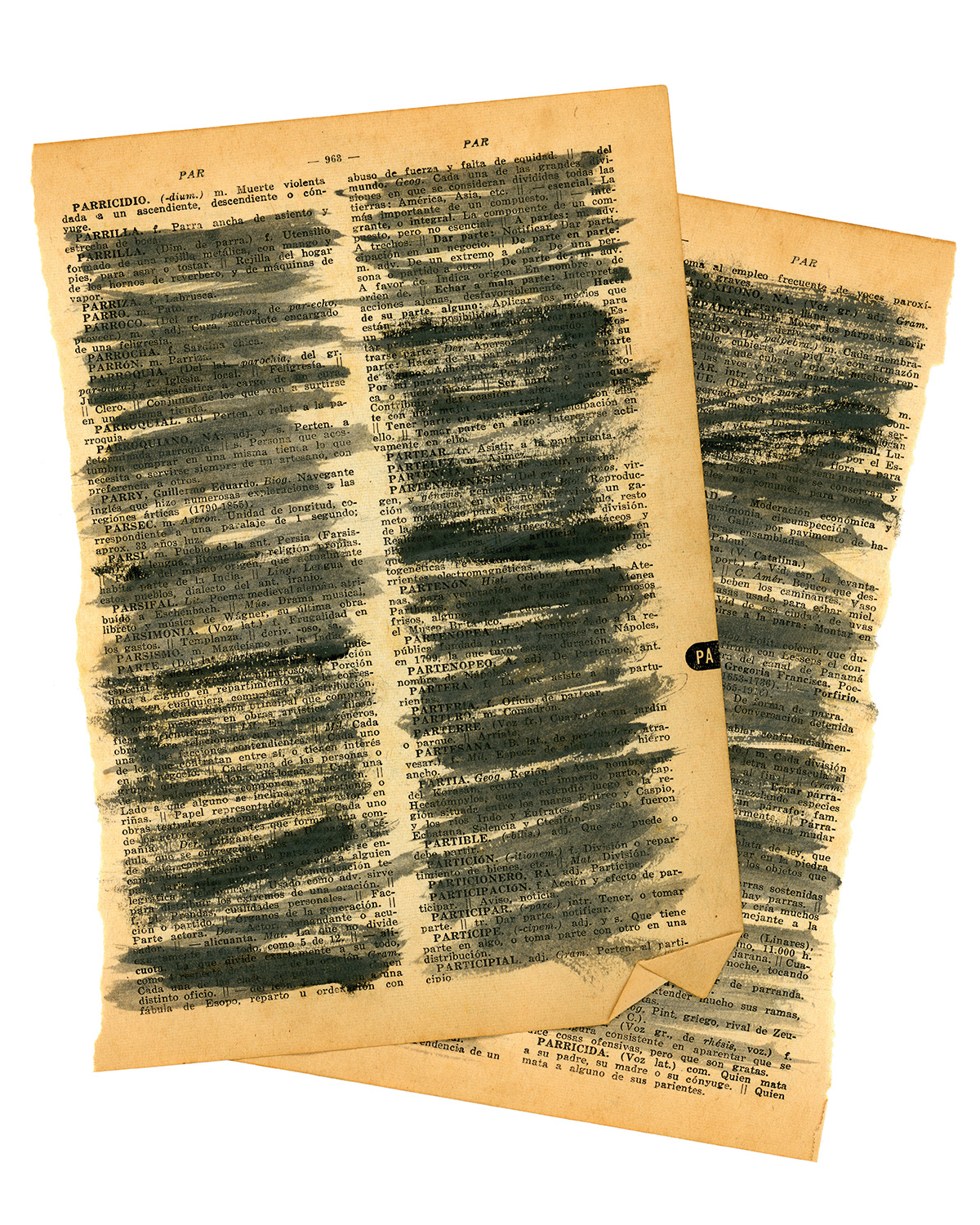

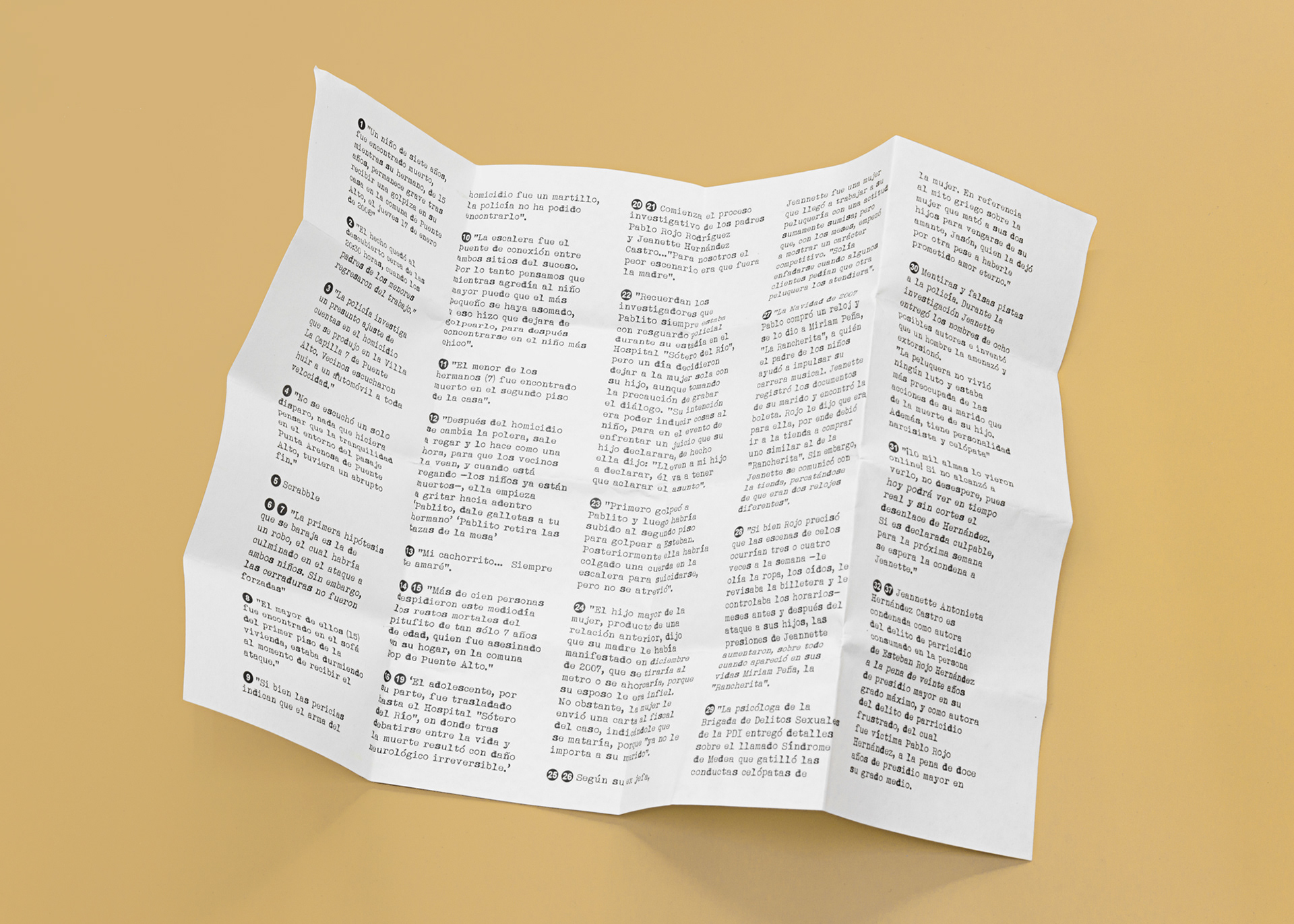

'Medea' evidences the prejudice, cruelty, and privacy violation to which the press and public opinion exposed a middle-class family, violating their integrity through unscrupulous and sensationalist tracking.

Tragic Women by Jorge Díaz

Biologist, writer, and sexual dissident activist

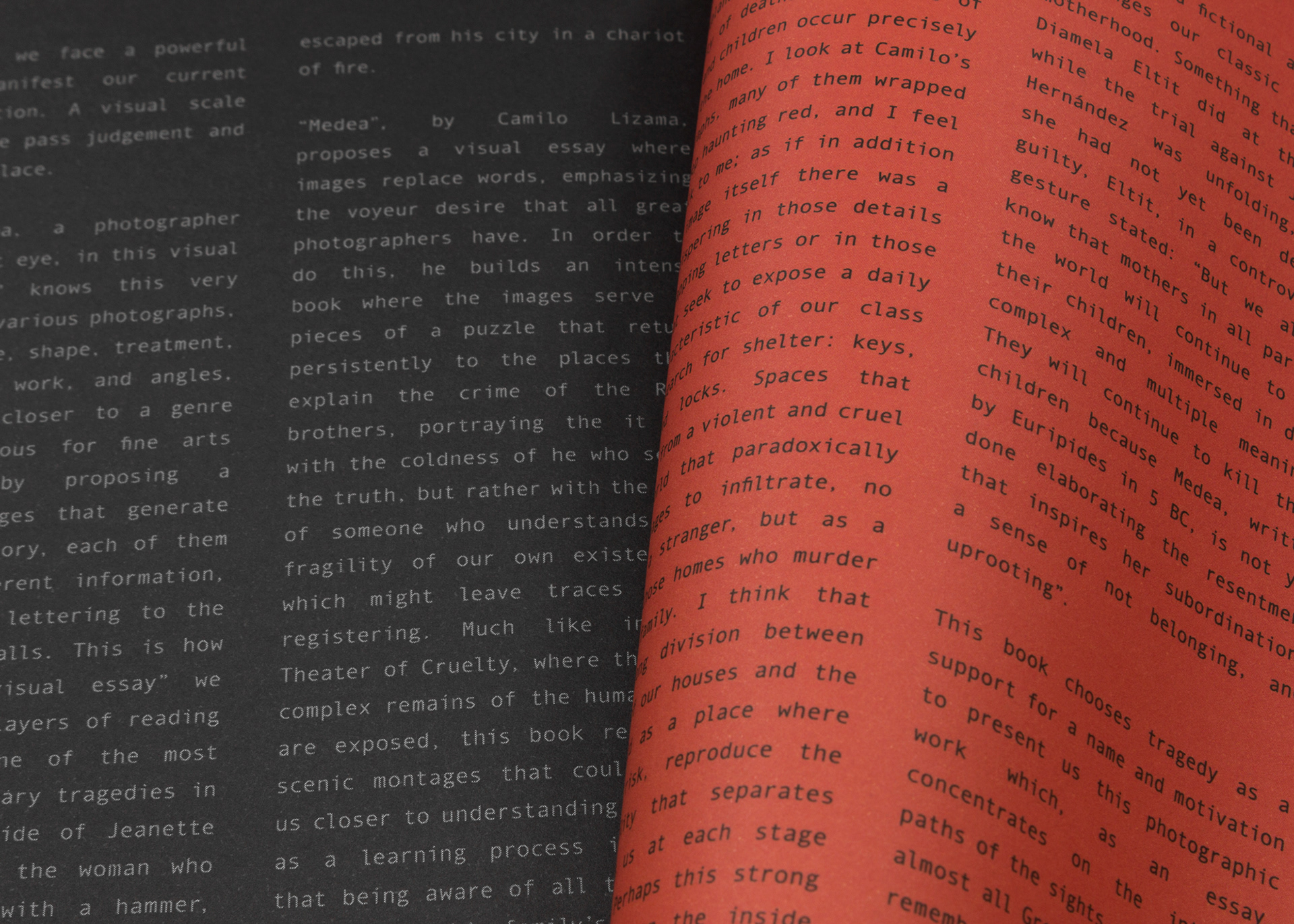

The essay as a genre dismisses some current conventions of knowledge by giving itself the necessary time to expose ideas without the haste that the academic language uses in its scriptures cloistered in disciplines and the authors that hierarchize the ways of thinking. This hegemony of atomized writing is a problem that we must take very seriously because it prevents the wide spread of pieces of work across the social and political spectrum. The essay represents a possibility of expression, tentative, and conjeture, exposing its own creation processes with a poetic that escapes from that language that forces us to always seem transparent, clear subjects, without opacities or contradictions. As if the biography that constitutes us, with its dissimilar geographies, migrations, and experiences, had not carved with pain and joy our images and words. Perhaps this is why the essay, as writing technology, attracts the attention of thinkers, activists, and artists who pose uncomfortable questions; because it forces us to stop and take another look to understand their productions, processes, and research. Furthermore, if to the density and poetry that the essay considers, reincorporate the power of photography as a language, we face a powerful tool to manifest our current power situation. A visual scale from which we pass judgement and establish a place.

Camilo Lizama, a photographer with a migrant eye, in this visual essay knows this very well: through various photographs, varying in size, shape, treatment, editing, color work, and angles, he brings us closer to a genre quite promiscuous for fine arts photography, by proposing a variety of images that generate a fragmented story, each of them delivering different information, from the press lettering to the colours of the walls. This is how through this visual essay we enter different layers of reading and focus on one of the most complex contemporary tragedies in Chile, the parricide of Jeanette Hernandez Castro, the woman who struck her sons with a hammer, killing one and seriously injuring the other, all a product of her jealousy for her husband. This woman has been called the chilean Medea, evoking the story of the woman in Greek mythology, who murdered her children and several other members of a certain monarchy in revenge for the deceit of her husband, Jason, who was engaged with a wealthy girl and escaped from his city in a chariot of fire.

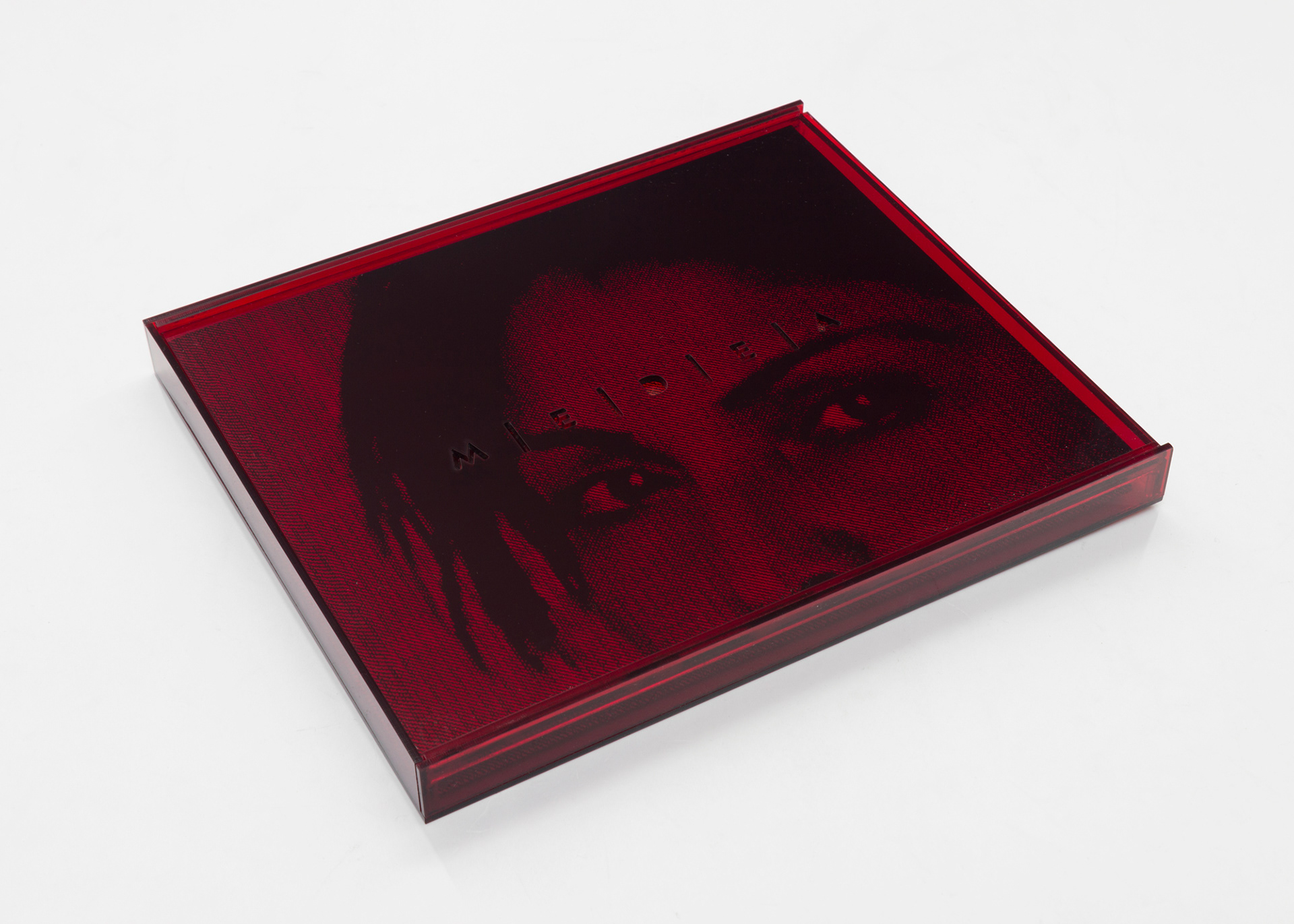

From the most radical currents of the feminist thought, there has always been a critique towards our current concept of family. Simone de Beauvoir, one of the most important thinkers of the modern day, declared that family is a nest of perversions as an explanation of why the vast majority of deaths and abuses of women and children occur precisely within the home. I look at Camilo’s photographs, many of them wrapped in a deep haunting red, and I feel they talk to me; as if in addition to the image it self there was a voice whispering in those details of overlapping letters or in those looks that seek to expose a daily life characteristic of our class and our search for shelter: keys, doors, and locks. Spaces that shelter us from a violent and cruel outside world that paradoxically always manages to infiltrate, no longer as a stranger, but as a member of those homes who murder their own family. I think that such a strong division between the inside of our houses and the outside world as a place where life is at risk, reproduce the binary mentality that separates and classifies us at each stage of our lives. Perhaps this strong classification between the inside and the outside -situation that Caribbean immigrants in our country are fortunately dismantling -constitutes the first action that triggers all local tragedy.

Medea by Camilo Lizama, proposes a visual essay where images replace words, emphasizing the voyeur desire that all great photographers have. In order to do this, he builds an intense book where the images serve as pieces of a puzzle that return persistently to the places that explain the crime of the Rojo brothers, portraying the it not with the coldness of he who seeks the truth, but rather with the eyes of someone who understands the fragility of our own existences, which might leave traces worth registering. Much like in the Theater of Cruelty, where the most complex remains of the human mind are exposed, this book recreates scenic montages that could bring us closer to understanding tragedy as a learning process in hopes that being aware of all the steps that led to this family’s downfall we will find the cathartic moment that purifies our passions of the spirit.

This visual essay represents an uncomfortable visit to a horror story from afictional angle that challenges our classic ideas of motherhood. Something that writer Diamela Eltit did at the time; while the trial against Jeanette Hernández was unfolding, when she had not yet been declared guilty, Eltit, in a controversial gesture stated: But we already know that mothers in all parts of the world will continue to kill their children, immersed in dark, complex and multiple meanings. They will continue to kill their children because Medea, written by Euripides in 5 BC, is not yet done elaborating the resentment that inspires her subordination, asense of not belonging, and uprooting.

This book chooses tragedy as a support for a name and motivation to present us this photographic work which, as an essay, concentrates on the intricate paths of the sights and eyes as do almost all Greek tragedies. Let us remember Oedipus, King of Thebes, who tore his eyes after he learned that his wife was his own mother and that he had killed no less than his own father. Oedipus takes his eyes but still the images remain there because sight, the visible and what cannot be seen are very present significations in the decisions made by Camilo to narrate the tragic story of Medea.

I heard very recently on television that after the crime the son who survived with neurological injuries did not see his father again, and instead looked for shelter with his mother’s family. This son, despite his brother’s death and the physical consequences of his mother’s hammering – half of his body paralyzed and cognitive failures – continued to visit her in jail and managed to request a special permit for her to go with him to his graduation from a technical school in Maipú. Thus, what happened after the apparent ending of this case is very complex and Greek tragedies, which represented subjects of certain royalty, no longer suffice to understand our histories of damage.

There will always be a Latin American mismatch that takes us away from the circular, predestined and super organized plot that tragedies from Sophocles to Shakespeare seem to follow. In times when the visibilization of the violence that women have always enduredis necessary, it is interesting and risky to commit visually to the case of a woman who murdered her children, since this takes away the focus of the traditional representation of women as good wives and mothers.

In his book “Medea”, Camilo Lizama is a daring visual essayist who set designs, focuses details, and captures press files while walking around houses and places, showing us that families and their crimes always have more complex stories. Because it may be through photography and essay that we can find some explanation for the meaning of life and the passion of these tragic women who continue to question our present way of living and surviving.

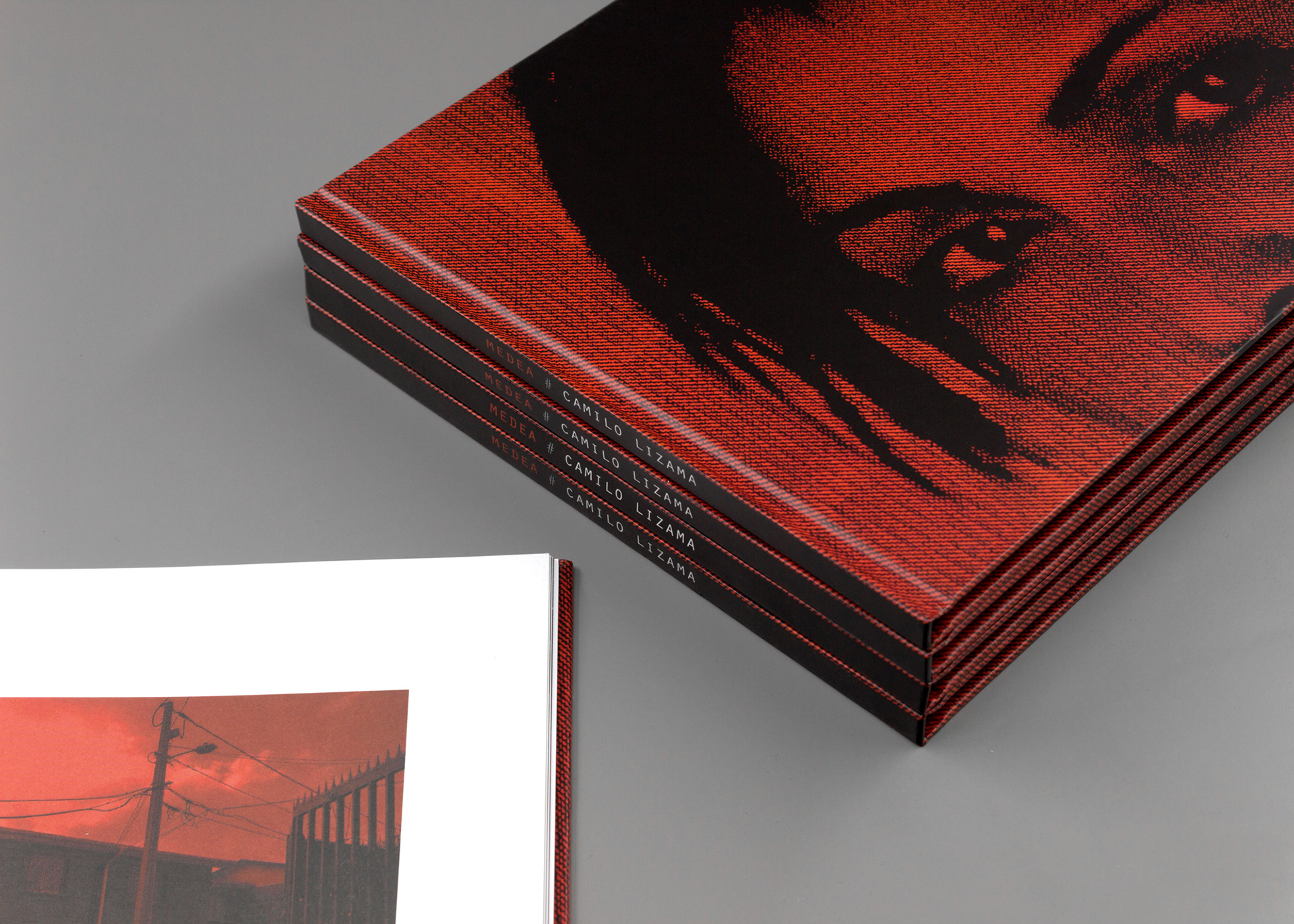

REGULAR EDITION

Language : Chilean

Hardcover

26x21 cm

48 pages + 3 inserts

Bond 140 grs

Printed in Santiago, Chile

isbn: 978-956-368-927-3

Hardcover

26x21 cm

48 pages + 3 inserts

Bond 140 grs

Printed in Santiago, Chile

isbn: 978-956-368-927-3

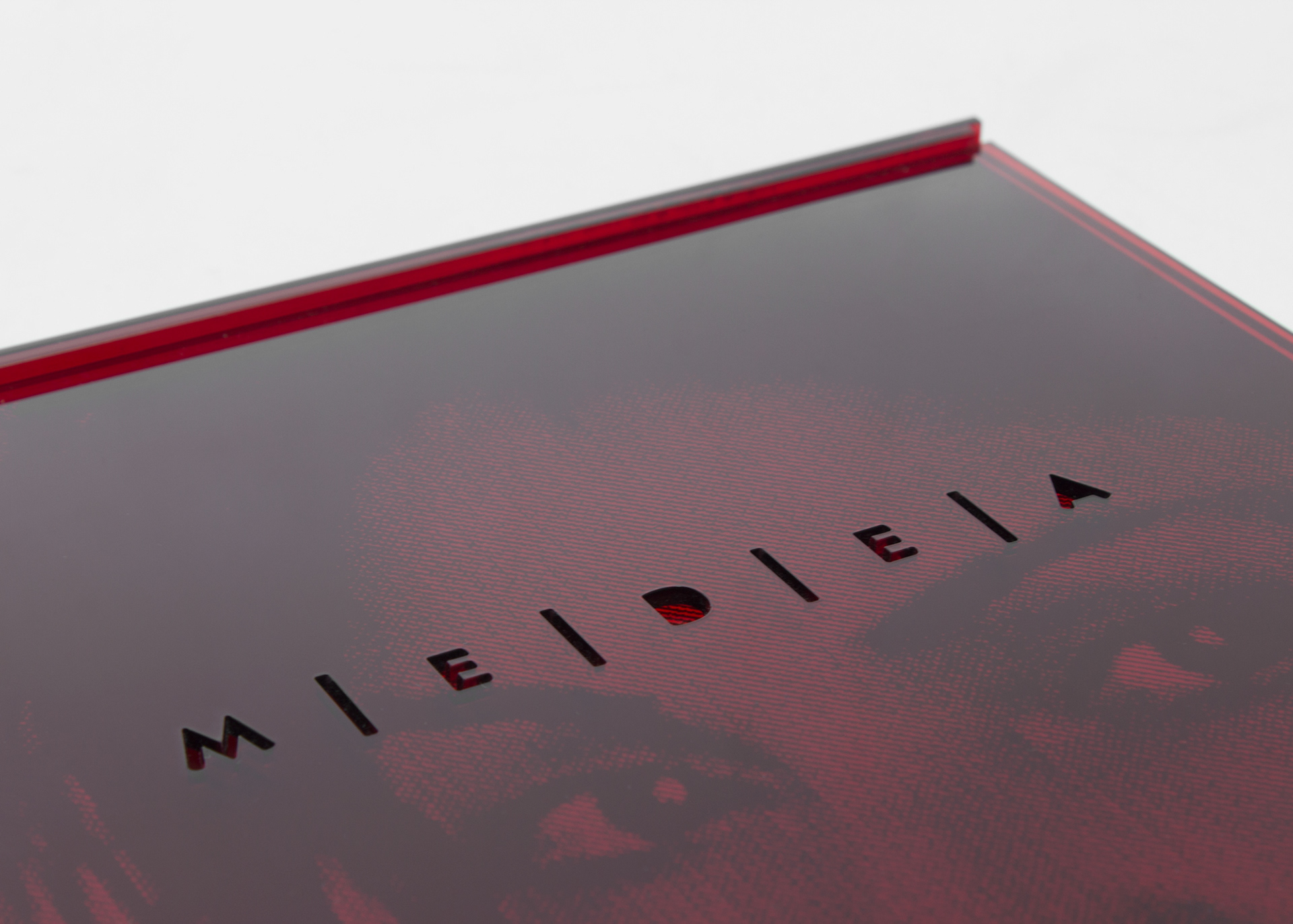

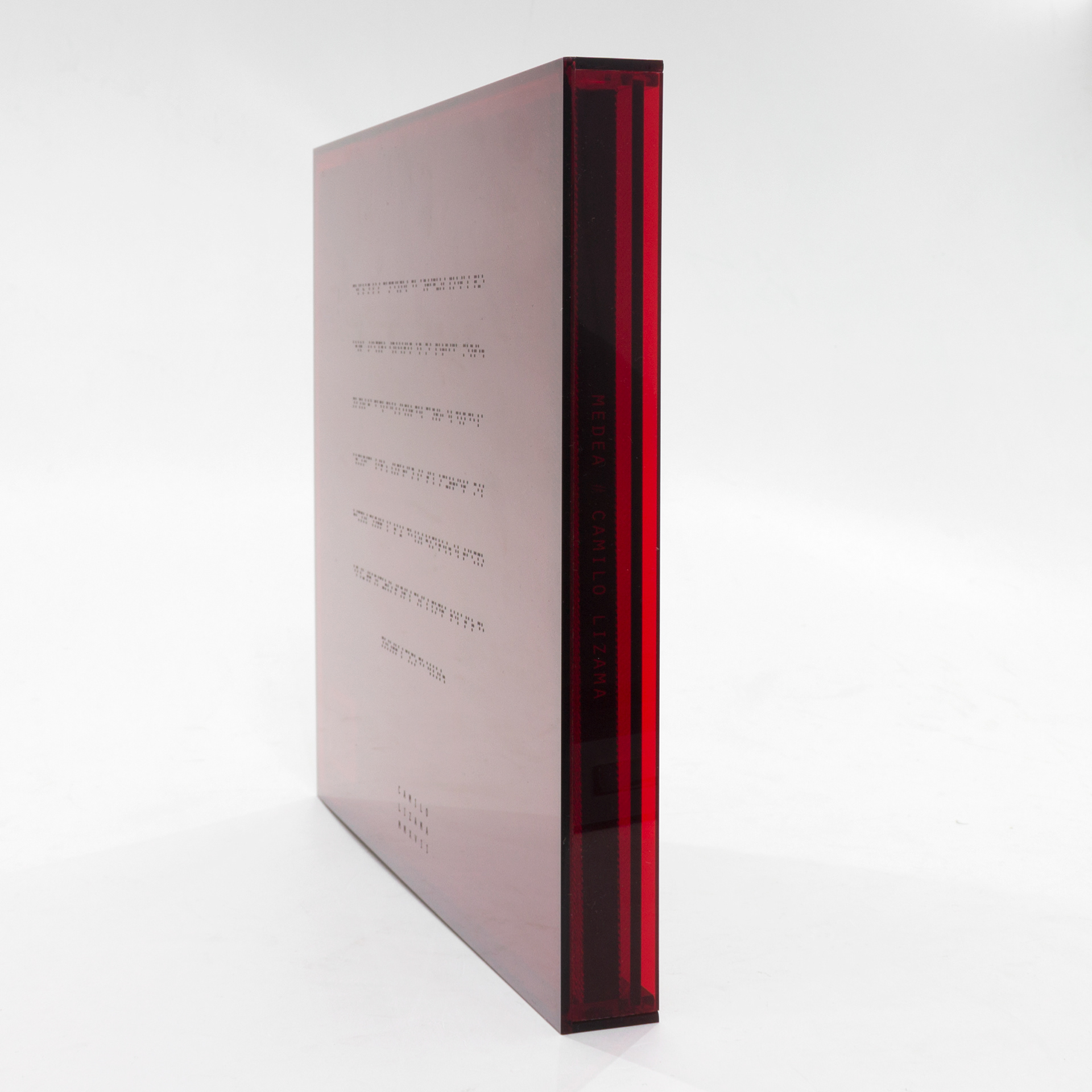

SPECIAL EDITION

Red Acrylic Handmade box

Risograph Canson Dessin 160 grs. 16x25 cm

Photo Hahnemühle Performance Satin 240 grs. 12x17 cm

Trial Audio-CD

Hammer keychain

Risograph Canson Dessin 160 grs. 16x25 cm

Photo Hahnemühle Performance Satin 240 grs. 12x17 cm

Trial Audio-CD

Hammer keychain

SOLD OUT

Photos by Diego Argote